Since I have broadly touched on the topic

of whether our climate is getting more extreme, I will now turn to look at the

trends in natural disasters over the years. However, before we begin to look at

the stats, let’s begin this post with the second episode of Disaster Bite on

the devastating earthquake that struck Bohol, Philippines just last Tuesday 15th

October 2013.

-----

Disaster Bite: Bohol Earthquake

|

| Epicenter of Bohol earthquake. Source: Inquirer News |

- 7.1 (previously reported as 7.2) magnitude on the Richter Scale

- Epicenter was at Bohol (about 620m south-southeast of Manila), at a depth of 33km

- It struck on 08:12 (local time) on a Tuesday 15th October 2013, which also happened to coincide with a national holiday

- The earthquake was caused by a vertical movement of the East Bohol Fault

- Earthquake did not result in a tsunami

- The death toll has surpassed 100 on Wednesday, with the greatest fatalities in Bohol and Cebu provinces

- Many damaged buildings and stampedes were reported Bohol and Cebu

- Tremor triggered power cuts in both provinces

- Strongest tremor felt in the area in the last 23 years

More information:

-----

With reports saying that this was one of the deadliest quakes in Philippine history, which released

energy equivalent to 32 Hiroshima bombs, it seems like it has joined the ranks

of deadly natural disasters that have brought great tragedy to mankind in

recent years (think Hurricane Sandy 2012, Tohoku earthquake 2011, Haiti

earthquake 2010 etc.). A question that pops into my head right now is: are

natural disasters becoming more frequent, intense and devastating?

Frequency

|

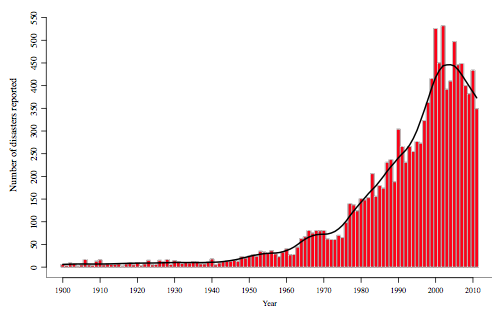

| Fig.1 Frequency of natural disasters from 1900 to 2010. Source: EM-DAT |

Based on the graph showing the number of

natural disasters reported from 1900 to 2011 (Fig.1) produced by The

International Emergency Disaster Database (EM-DAT), it does seem at first

glance that the frequency of natural disasters have increased tremendously over

the last century. However, this graph might actually be misleading as the

increase in number of natural disasters over the years could in fact be due to

better media reporting and advances in communications (Guha-Sapir

et al. 2004). Moreover, with the launch of agencies like Office of US

Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) and Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of

Disasters (CRED) in the 1960s and 70s, data collection on natural disasters

have markedly improved. Hence, what the graph is showing might in fact be the evolution

of the registration of natural disasters over time. Guha-Sapir et al. (2004)

thus suggested that it might in fact be more appropriate to review the

statistics of natural disasters over a shorter time span to spot trends (say

between 1980 and 2000). Even so, the frequency of natural disasters during

these 3 decades is still increasing. This might partly be due to the increases

in hydro-meteorological disasters as seen in Fig.2. Some reports attribute such

increases to climate change, which I will cover in the weeks to come.

|

| Fig.2 Worldwide polynomial trends for the four major types of natural disasters from 1900 to 2003. Source: Guha-Sapir et al. 2005 |

Intensity

Some studies have proposed that the

intensity of some types of natural disasters has increased over the years. This

include work done by hurricane expert Kerry Emanuel, who has shown that the

total North Atlantic and western North Pacific hurricane power dissipation have

more than doubled over the past 30 years (Fig.3) (Emanuel 2005). We’ll

discuss hurricanes in greater depth in future posts. However, for other types

of natural disasters such as earthquakes, it is much more difficult to spot any

trends in intensity over the years.

Vulnerability and devastation

Nonetheless, it

does seem that the impacts (e.g. loss of life, economic damages) of natural

disasters are increasing over the years. It has been proposed that this is due

to the increasing vulnerability due to large populations living in high-risk

areas as a result of population growth and urbanisation (Huppert and Sparks 2006).

Jackson

(2006) cites the example of Tehran, which has grown from being a small

village town to a megacity with 12 million inhabitants. This has greatly

increased the vulnerability of Tehran to earthquakes given that it is built on

an active fault system. In fact, in 2012, more than 300 were killed in twin earthquakes that rocked the region. Moreover, as our assets

increase, there is more to be lost when a disaster strikes. The UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction

(UNISDR) reported that for the first time in history, the annual economic

losses caused by natural disasters have exceeded $100billion for three consecutive

years (2010-2012). This is due to the major increases in exposure of our

industrial assets and private property to these disasters.

Based on the discussion above, it seems

that it is hard to conclude whether natural disasters have increased in

frequency and intensity over the past few years. However, we are indeed

becoming more vulnerable to natural disasters due to growth in population and

assets. Nonetheless, with the recent IPCC

AR5 report (2013) attributing some natural disasters to climate change as

well as a recent NOAA report (Peterson et al. 2013)

that attributed single natural disaster events to climate change, it is

interesting to see how the changing climate as (discussed in the previous post)

would have an impact on the intensity and frequency of future natural disasters. Stay tuned over the next few

weeks as I continue on my quest to unravel the links between the changing climate and natural

disasters.

Hey Joon, Nice blog! I have a few things i would like to say.

ReplyDeleteI know you're going to talk about hurricanes in a post latter on but i thought might say this now though. You mention that the intensity of tropical storms is increasing as demonstrated by Emanuel's work on his power dissipation index. As i understand it though this is a cumulative metric so your statement (and its implications) are a bit misleading. I think its not that storms are getting absolutely more intense (i.e. they are somehow now exceeding the highest storm category, i.e. 5 on the Simpson-Saffir scale, to now be like category 6+), rather its an issue of intensity frequency. So, i think there is evidence that there are now proportionally more category 4 and 5 storms relative to TSs, 1s, and 2s than there were in the past. See what i mean?

I think the key paper on this is Webster et al. 2005 - http://www.sciencemag.org/content/309/5742/1844.full.pdf

What's worth pointing out though (at least i think) is that work on hurricanes is severely hampered by data availability. The best sort of record there is starts with the satellite era (1970s) so its kind of officially unclear right now whether the proportional increase is statistically different from natural variability. Its just that in light of all the other work around global warming the conclusion that its happening seems more probable.

There's a really nice, really recent, paper on this by Kunkel et al, 2013. ftp://texmex.mit.edu/pub/emanuel/PAPERS/Kunkel_etal_2013.pdf

Last thing! There's also a really cool paper by Mendelsohn et al. 2012 (where et al. includes Emanuel) taking not about objective changes in storm intensity or power but rather about the impacts of these changes. So it combines changes in storms with changes in human vulnerability as people (generally) become richer. Whether thinking people will become richer is a rather naive assumption is another issue all together .....

I hope these points are constructive.

J.

Hi Josh! Really appreciate your comments!

DeleteFirstly, regarding the intensity of the hurricanes, yes I definitely agree with what you have pointed out. Indeed, storms of a higher category (e.g. 4 and 5) seem to be increasing in frequency as highlighted in the Webster et al. (2005) paper. Cat 4 and 5 hurricanes have, according to the paper, almost doubled in number from the 1970s to the past decade. However, according to a paper by Elsner et al. (2008), they also suggest that the intensities of the strongest tropical cyclones have been increasing as well. Nonetheless, their strongest signals come from the Atlantic Ocean, which cause some papers like Knuston et al. (2010) to counter-suggest that the increase in hurricane intensity might actually be due to the high multidecadal variability in the basin, especially since the data spans only a short period of time (1980s to 2000s). What are your thoughts?

Elsner et al. (2008) http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v455/n7209/abs/nature07234.html

Knutson et al. (2010) http://www.nature.com/ngeo/journal/v3/n3/abs/ngeo779.html

Secondly, regarding data availability. Yup I agree that work on hurricanes are hampered by data availability and that the rise in both hurricane frequency might actually be a statistical artifact. Came across this reading by Landsea et al. (2010) as well as his opinion paper published on the NOAA website (links below) that show that satellite technology has been advancing over the years, becoming much more sensitive and detecting more short-lived tropical cyclones. So the increase in hurricane frequencies over the years might be due to that some hurricanes now being included in databases were missed out previously.

Landsea et al. (2010) http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/landsea-et-al-jclim2010.pdf

His opinion paper http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/Landsea/gw_hurricanes/

And yea on the vulnerability of societies towards natural disasters, I guess ultimately what matters might not how strong or how frequent a natural disaster might be but how vulnerable we are to them. A disaster of a smaller intensity that strikes a highly vulnerable society might inflict more damage than a disaster of a higher intensity that strikes a more resilient society.

P.s. Sorry for the late reply, been really busy over the weekend. Thanks for taking the time to check out my blog :)

As this post relates to my over theme about communication and Climate change I had to comment! It made me think back to a trick question on an exam in a natural disasters module I have taken. The question was why were the amount of tornadoes increasing rapidly in central plains of the US during a certain time period. The answer was because no one lived there before to see them! :)

ReplyDeleteJ

Hi! :) Yea I think this applies to many other types of natural disasters as well (or actually, come to think of it, anything that deals with counting e.g. a species of animal/insect). As technology advances and observational practices improve, we are able to detect and document these phenomena better, leading to an apparent rise in frequency of disasters, when may be in reality there hasn't been an actual rise in frequency!

DeleteAs far as I'm aware (i.e. i could easily be wrong) its Knutson's paper that most research would currently back. It will be great to see your post on exactly this in the future!

ReplyDeleteAlso, while we're on the subject defiantly check out hypercanes. There is a hypothesis that one of these caused the mass extinction that killed of the dinosaurs.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypercane

J.